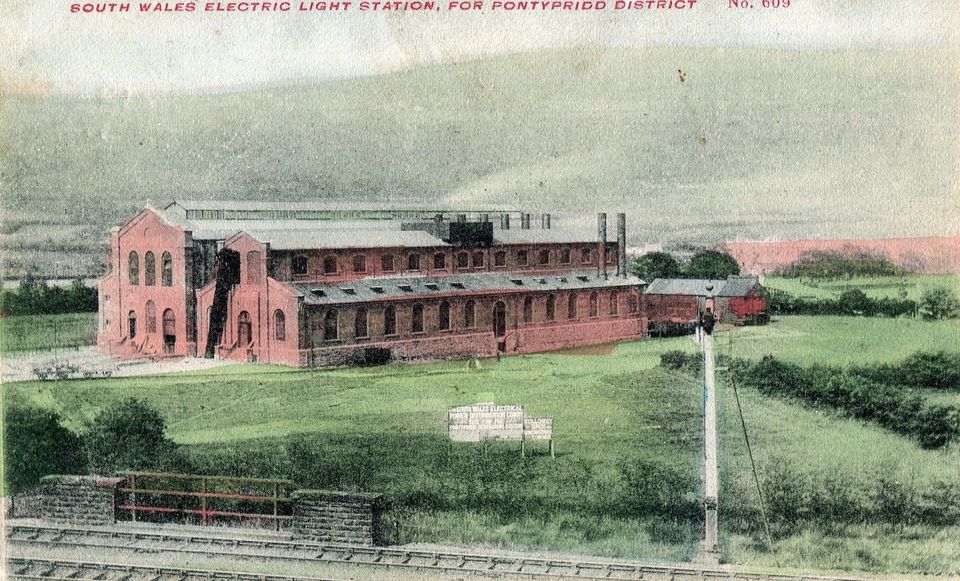

Peter initially had a mining pension of 10 shillings and 6 pence a week, but settled for a lump sum of £300. He was still living in Barry Road with his mum, who supplemented their income by taking in washing for people who were more comfortably off and living on Graigwen. They found it very hard to make ends meet, and Peter needed a new job. Like many other local men and women in the post-war period, he found work at the newly-established Treforest Industrial Estate. He trained first as a welder/fitter at the power station, and later worked at Fram Filters in the Simmonds Aerocessories building, eventually going to Llantrisant when Fram Filters moved there.

Peter was always a committed Labour Party supporter. He recalled marching through Market Square as a 14-year-old with his fellow miners during the 1921 miners’ strike. This political commitment stayed with him throughout his life. At Fram Filters he became Amalgamated Engineering Union (AEU) shop steward, convenor and Trades Council representative for 22 years. He took great pride when the AEU’s leader, Hugh Scanlon, named his branch as the third best nationally. On Peter’s retirement there were 500 people in the factory canteen to say goodbye, and the send-off brought tears to his eyes.

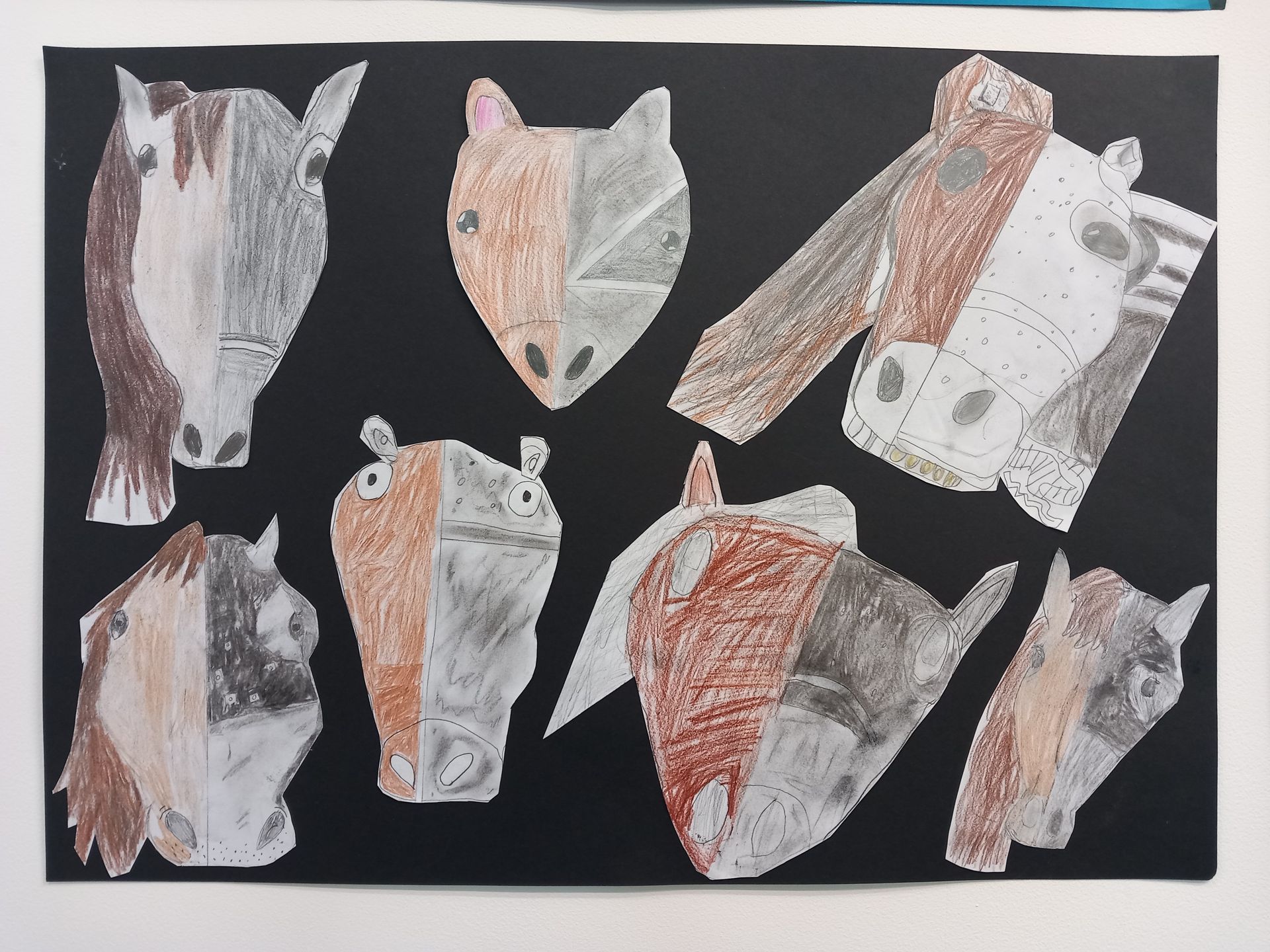

Some of Peter’s memories of old Pontypridd did this same...through laughter. He remembered the horse-drawn Dr. Griffith’s tramroad that brought coal from Trehafod to join the canal at Treforest. The canal was a major attraction for the local kids who might cadge a short ride on one of the barges, or use the water course as an informal swimming pool.

One day a local printer, by the name of Percy Phillips, somehow managed to entangle himself in a canal barge tow rope, with the result that his false teeth popped out of his mouth and disappeared into the murky water. Looking at the children gathered around him, Percy announced, ‘I’ll give anyone who jumps in a halfpenny, and the one who finds the teeth sixpence.’ Before you could say ‘Jack Robinson’, forty or so kids were in the water, trawling the depths for the missing molars.

Alas, to no avail. The diving dentures were never traced. Percy Phillips trudged sadly home minus his teeth, and with his wallet much lighter.