Blog Post

In the second installment of our blog looking at the Museum's oral history collection, Assistant Curator Dave Gwyer turns his attention to the nearby village of Cilfynydd, reflecting on the theme of belonging, through the stories of two women who became pillars of their community.

The first edition of this blog, based on interviews with elderly Pontypridd residents recorded during the late 1980s, featured people from the southern end of town – Graig, Treforest and Hawthorn. With this second instalment I redress the balance, and look north to Cilfynydd.

I've always been fascinated by how the people of the Valleys have such a distinctive sense of place and hierarchical scale of identity. They may not be unique in this, but the trait is certainly developed into a fine art here. The seemingly simple question, 'where do you come from?' will draw a range of replies depending on the questioner and audience. For those unfamiliar with the niceties of local geography, someone might be described as a 'Ponty boy or girl'. To those in the know, the individual village within the town will have much more resonance and meaning. To outsiders the boundaries of each of these places are invisible, but to the locals they are as obvious as controlled border crossings. You're brought up with it.

I still remember my primary school sports days in the Rhondda, where the five local schools based within less than two miles of each other went head to head in bitter rivalry. I still get a glow of satisfaction out of the fact that for the four years I was there, Ton Pentre Primary came top of the pile! Later, and across one of those invisible borders, I recall the traditional Boxing Day rugby match, between Treorchy and Treherbert, was less about a spot of fresh air after the excesses of Christmas, than a way of settling inter-village grievances. It always drew an impressive crowd, and more often than not descended into a mass brawl - the score was calculated by the number of those sent off.

This extended preamble, and meditation on local identity, is by way of saying that I believe it's the very fact that these Valley communities were built from nothing in such a short time that gives them their special sense of place. When nearly everyone is an outsider you need to pull together to make things work.

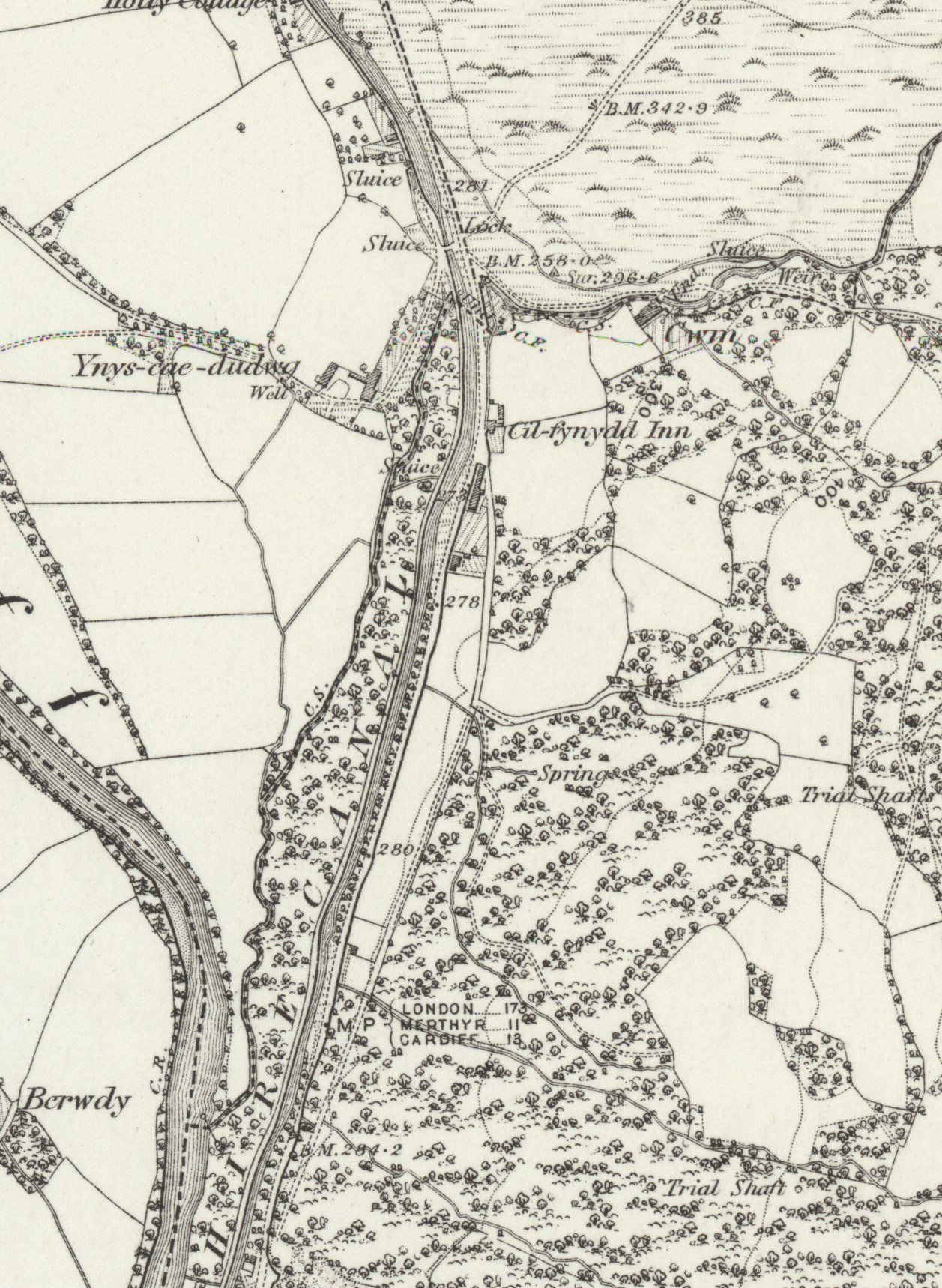

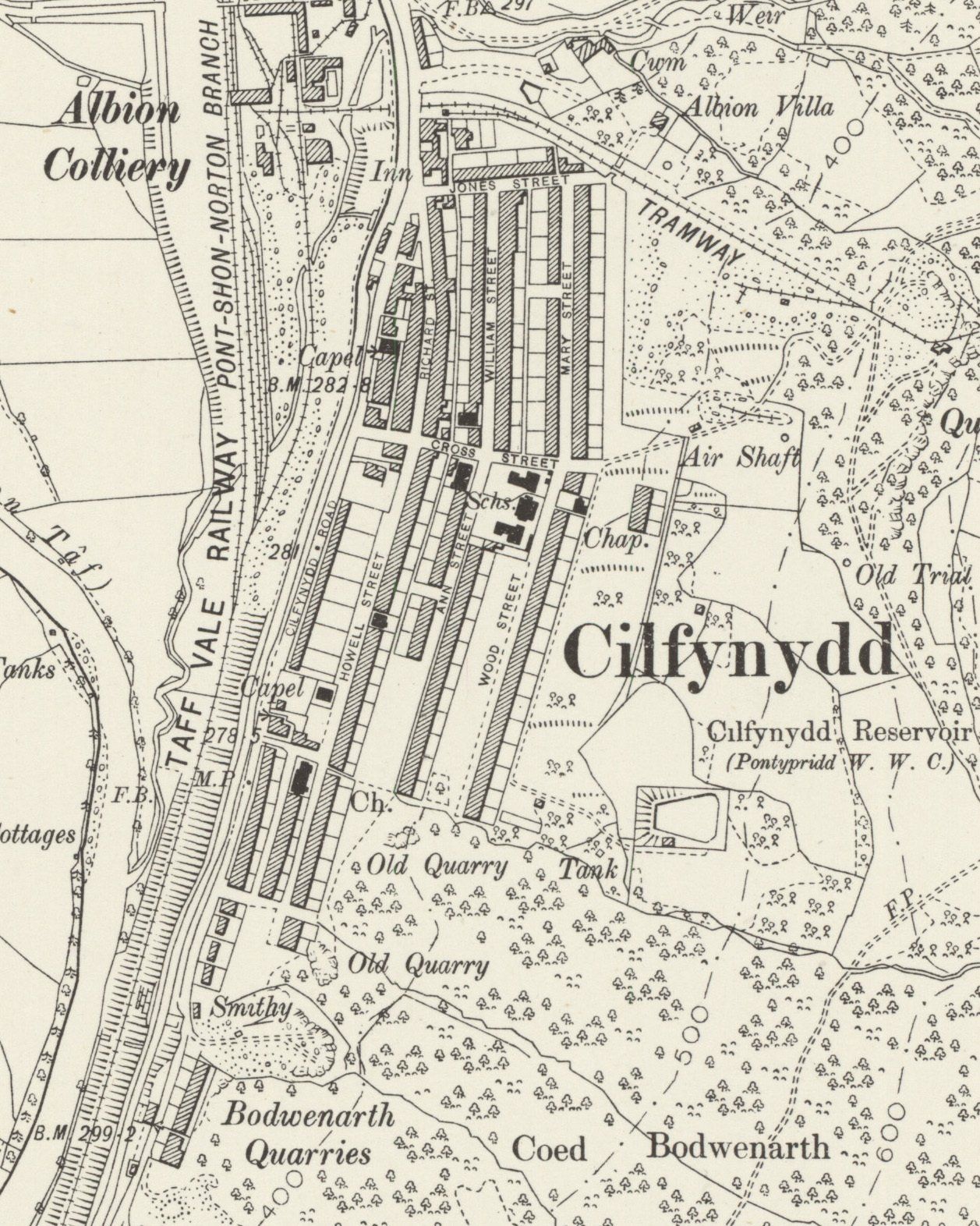

Cilfynydd is a case in point. It grew as an archetypal pit village, based around the Albion Colliery which started producing coal in 1887. As late as the 1870s the district’s population was only around 100 - by 1900 it was more than 3,000. The incomers arrived from other parts of Wales, but also from further afield where their lives had been very different.

They included Mrs Humphries, who was born in Bristol in 1892. By special dispensation, she'd left school at 11 and spent 3 years as companion to a Miss Dobbie. She remembered this time fondly. Miss Dobbie's brother was a young lieutenant, William, who was friendly with David Churchill, a cousin of Winston Churchill. Whilst on leave William and David often stayed with Miss Dobbie at her cottage in the West Country. After a long and distinguished military career, General William Dobbie became governor of Malta when it came under siege during the Second World War. Mrs Humphries stayed in touch with the Dobbie family until General Dobbie's death in 1964.

What changed her life forever was the fact that her father lost his job in 1906. The lure of work and greater prosperity convinced him to uproot his family of 7 to the booming South Wales coalfield. They travelled by boat from Hotwells in Bristol and landed in Cardiff, from where they transferred by tram and train to Pontypridd, and eventually to Cilfynydd. In a Cardiff tearoom the family drew attention from the locals. 'My word,' one remarked, 'you've got some rosy-cheeked, fine-looking, children. Where are you going?' Her father replied, 'I'm going to work in the pit, so I'm taking them to a place called Cilfynydd.' 'Oh,' the stranger said,' they won't have faces like that in 6 months time.' 'Ah, that's where you're wrong,' her father came back, 'God's air is as good on the mountains as it is in the country.' Despite his positivity, you can't help wondering about his family's feelings as they travelled to make their new home in Cilfynydd. But, like so many others, they adapted to life there, and became part of the thriving, youthful, community.

Mrs Humphries found work as a live-in nanny in Cardiff, but when the First World War broke out she returned to Cilfynydd, working as a conductress on the tramcars, just like Gertie Williams from Treforest who featured in the first of these blogs (Gertie remembered Mrs Humphries well, and was very pleased to hear she was still alive). Mrs Humphries married and spent the rest of her life in Cilfynydd, becoming a pillar of the community, taking a job at the doctor's surgery, joining the St.John's Ambulance Brigade and the Royal British Legion, where she was the local branch chair and standard bearer for 37 years. As she got older she joined the local pensioners group, organising events and trips for its members. Looking back on her life she reminisced...'You see, I enjoyed outside life...my life has been a full life all the time. Well, here I am retired now (at 95!). I still go to the old age and I'm still going to do all I can while I can, until my time is over. And then, like my father used to say, "death is only a train journey, someone is getting off at every platform, and there's always someone there to meet you".'

Mrs Humphries arrived in Cilfynydd as an outsider, but she soon became part of the fabric of the village, as did so many others who came together there at the start of the 20th century.

People like Miss Christine Blizzard. Schools are vital building blocks of any community, especially one being set up from scratch. Miss Blizzard was born in Cilfynydd at the end of the 19th century. She passed a scholarship to attend the grammar school and then went to Barry Teacher Training College, before returning to the village as a certificated teacher to take up a post in Cilfynydd Primary School after World War 1. At the time the school had over 300 pupils, and Miss Blizzard had a class of 53.

Discipline was strict and learning was by rote. She remained a teacher throughout her working life. That she never married is a reminder that in those days women teachers were expected to be single - if you married you gave up your job. Through her class passed hundreds of little boys and girls, including Merlyn Rees, Labour Home Secretary between 1976 and 1979, as well as the two world-class opera singers who were both born in William Street - Sir Geraint Evans and Stuart Burrows.

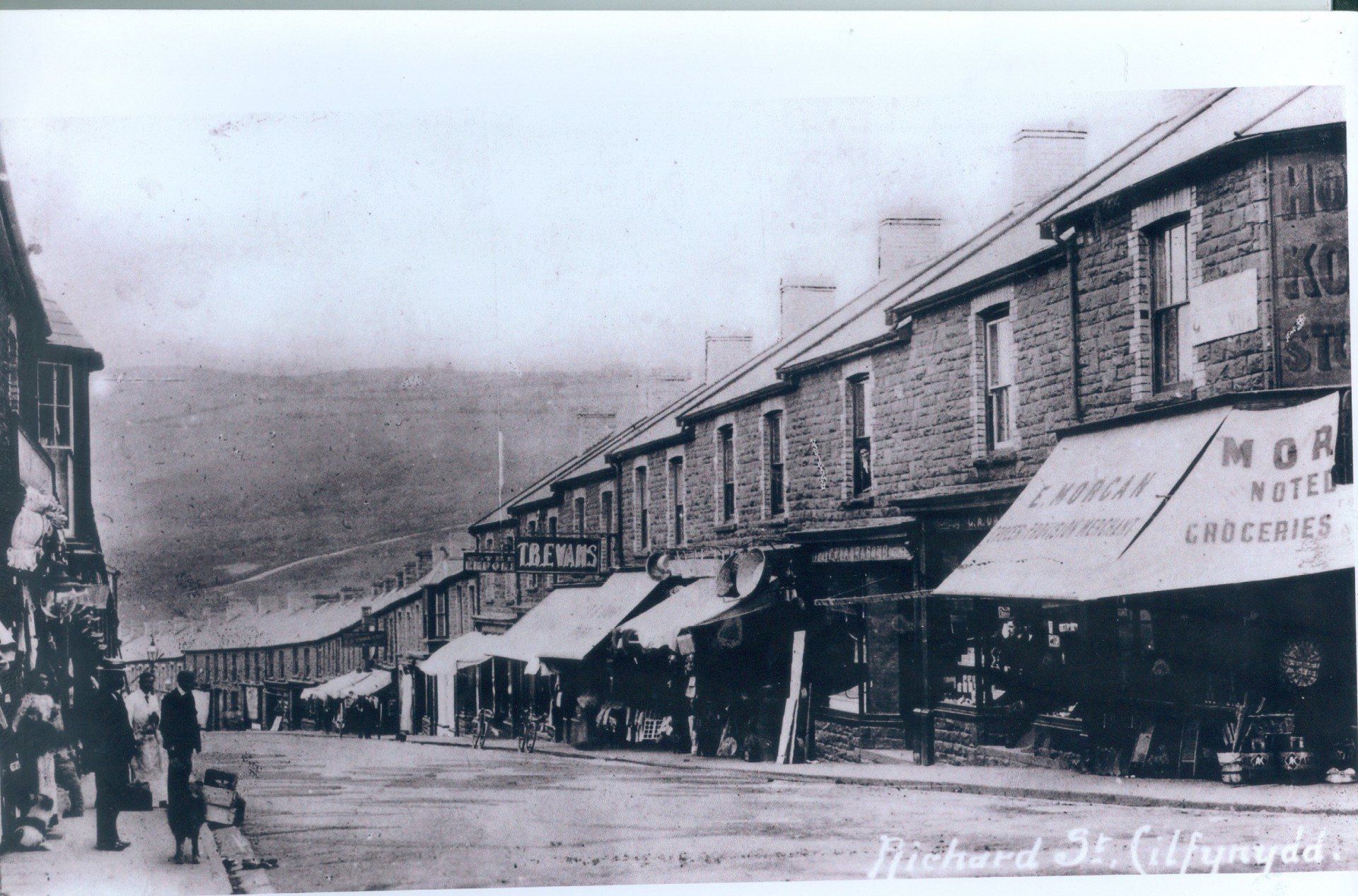

At the time Cilfynydd was very much a self-contained community. A trip to Pontypridd was a special outing, but most of life's necessities, and some luxuries, were available on your doorstep. Miss Blizzard recalled Richard Street as an elongated Aladdin's Cave of shopping treats, including 3 drapery shops whose clientele reflected which chapel they attended - Welsh or English Wesleyan, or Presbyterian - giving a whole new meaning to religious predestination!

Whatever their denomination, one of the things many of the newly arrived settlers wanted most was their own place of worship, which is why Cilfynydd had so many chapels and churches. Miss Blizzard attended chapel happily three times on a Sunday and one week night service too, although she recalled her younger brother was less enthusiastic each Sunday, as any sort of play on the Sabbath was frowned on.

Central to the life of the village was the pit, and both Miss Blizzard's father and brother were employed at the Albion Colliery. Her father managed all the coal and waste traffic as it came to the surface, what was called 'Boss on top'. He was a stickler for punctuality with his workforce. One day an Irish surface worker turned up half an hour late, and was asked sternly where he'd been. In thick Irish brogue he replied, 'Well you see boss, it was like this...my 2 sisters are away, so I had to get up and call meself!'

The Irish were just one ingredient in the Cilfynydd melting pot. People came from far and wide and built a community which survived the trauma of the Albion Colliery explosion of 1894, when 290 men and boys died. The pit finally closed in 1966, and the local high school now stands on its site. The mining memorial there reminds us not only of the sacrifice of the 290, but also of the courage, strength and perseverance of all those who've contributed to the story of Cilfynydd.

GET IN TOUCH

Contact Us

Thank you for contacting us.

We will get back to you as soon as possible.

We will get back to you as soon as possible.

Oops, there was an error sending your message.

Please try again later.

Please try again later.

OPENING TIMES -

- Monday

- -

- Tuesday

- -

- Wednesday

- -

- Thursday

- -

- Friday

- -

- Saturday

- -

- Sunday

- Closed

Sign up to our mailing list

Thank you for subscribing.

Keep an eye out for updates from the Museum in your inbox!

Oops, there was an error subscribing.

Please try again later.

Enter your email address to subscribe and receive museum news.

ADDRESS

Bridge Street

Pontypridd

Rhondda Cynon Taff

CF37 4PE