In the fourth installment of our blog looking at the Museum's oral history collection, Assistant Curator Dave Gwyer takes a look at local identities through the lives of three women from Phillip Street on the Graig, Pontypridd.

A sense of place

In an earlier blog post in this series I wrote about the strong sense of local identity forged in the South Wales Valleys. This piece emphasises that point. It’s based on the taped reminiscences of three women who were brought up in Phillip Street on the Graig, Pontypridd. The interview was recorded in 1989, and has taken a good deal of unravelling as it was conducted with all three simultaneously! What shines through is their emotional attachment to the tight-knit community forged on the Graig.

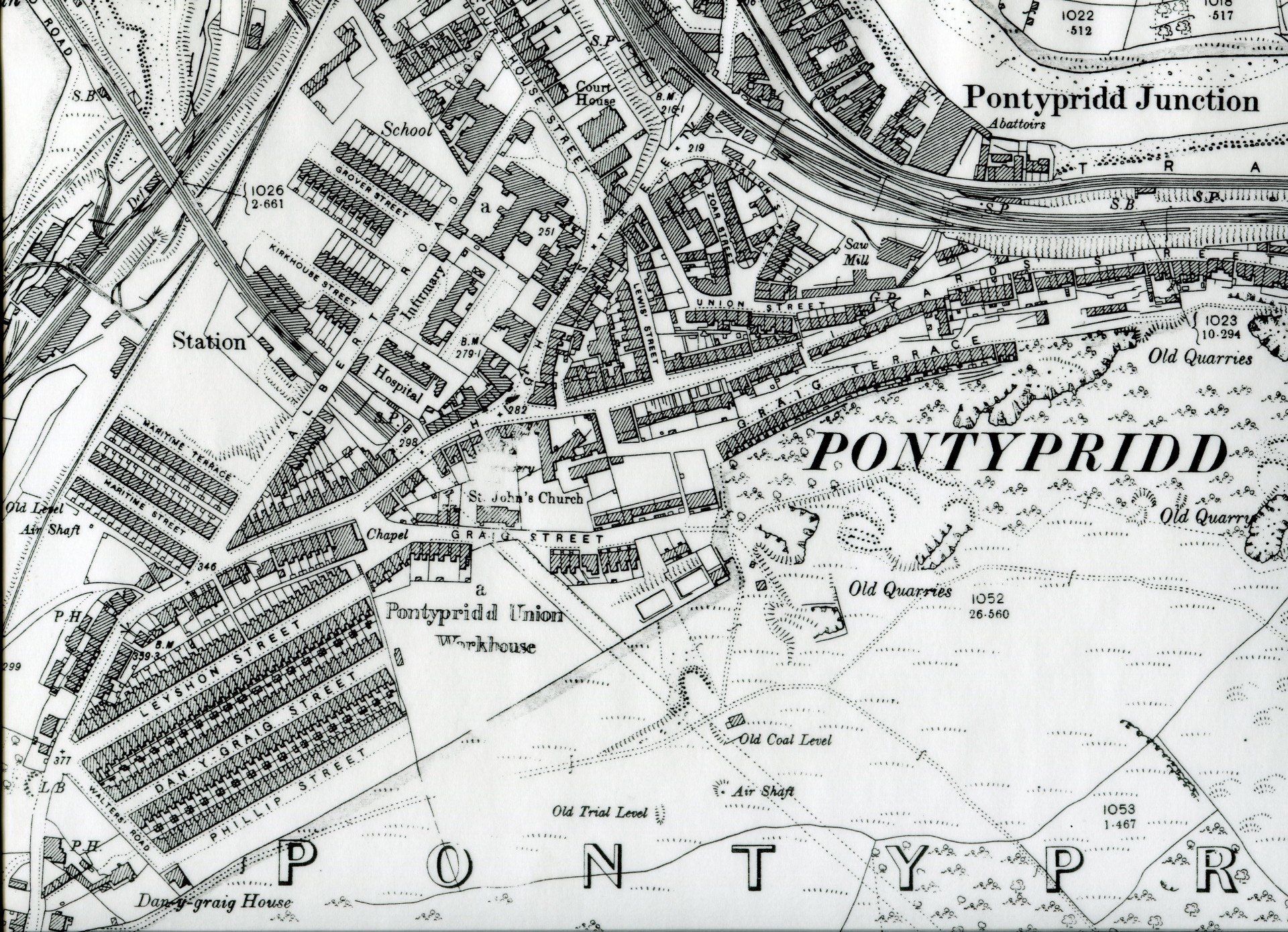

The Graig is one of the oldest districts of Pontypridd, and has always been a distinct place within the larger settlement. It straddles the steep hillsides at the southern end of town, and is contained by the railway line from Merthyr to Cardiff which opened in 1840. The old parish road to Llantrisant winds its way steeply uphill at this point, and the oldest houses on the Graig originally clustered alongside it. The women recalled that the first name for area was Llanganna, a name you'll find on the 1875 Ordnance Survey map. I seem to recall reading that this name derives from that of the place of origin of an old woman who was one of the district's early settlers - Llanganna is in the Vale of Glamorgan, near Bridgend.

Some of the earliest houses here were constructed in the 1840s, and many of them were 3 storey buildings, often occupied by several generations of the same family. Businesses and industry also concentrated here to be close to the railway. As the Graig grew, and more houses were squeezed into a limited amount of space, the street pattern became a warren of closes and alleys. The population continued to increase and more terraces were built, clinging precariously to the steep hillsides overlooking the town. Pubs abounded and most streets had their own 'corner shop'.

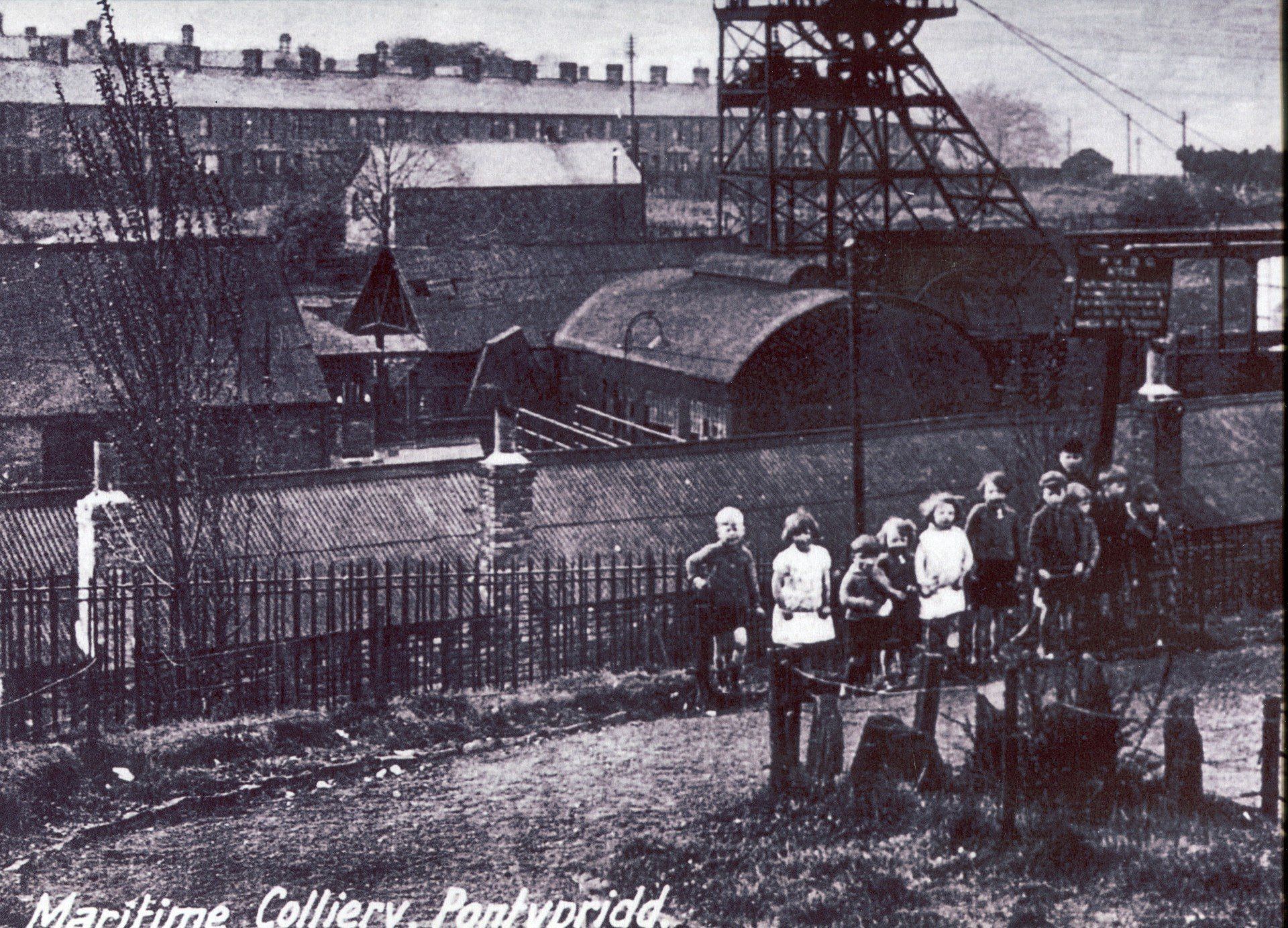

Coal mines such as the Newbridge Colliery (1845), and the Pontypridd Colliery (later Maritime Colliery), opened nearby in the Gelliwion Valley providing local employment. All this made the Graig a bustling, vibrant, place which soon fostered a well-developed sense of community.

1900 O.S. map of the Graig

Time and again, throughout their joint interview, Edna, Thelma and Ivy returned to this shared sense of place, family and friends. In fact, they described their relationship as being like family. Whenever they got back together they were comfortable in each other's presence, and their fund of shared memories came tumbling out. Their childhoods were not wealthy in any material way, but their lives were enriched by the love, comfort and security of a happy upbringing. They described Phillip Street as a rough and ready nursery, but the best place you could ever grow up in for comedy. Street parties were common - not only to mark great national celebrations but as a matter of course. All the houses in their street would put a penny a week into a fund to pay for a regular get together. Jelly and fruit never tasted so sweet. A neighbour who was the first in the street to have a radiogram placed it in their open front window and, if it was a nice summer's night, the dancing went on into the early hours. The kids were allowed to stay up too.

Traditionally, the festivities were topped-off by a punch-up. During the 1840s the Graig attracted a large number of Irish settlers escaping famine in their own country. Two of their descendents were the most regular combatants - 'Little' Mahoney and Paddy O'Brien. After a few pints, Mahoney would roll-up his sleeves and challenge all-comers, 'Who wants a bloody fight then?' Paddy O'Brien was the most likely to take up his offer. At around 5 feet 6 inches, neither of them could be described as a heavyweight contender, and the fisticuffs always ended without malice. In fact, should anything happen to one or the other, or their families, they'd be the first in the queue to help in any way they could. This was true of most families on the Graig, who were always there for each other when times were hard.

Children playing outside the Maritime pit c1930

The threat of unemployment was a constant during the 1930s. A drop-in centre called the 'Bomb and Dagger' offered some respite for the unemployed. It contained a shoe repair workshop, and even a dancehall where the daily grind of existence could be forgotten briefly on a Saturday. Local jazz bands like the 'Foreign Legion' also lifted the locals' spirits.

Workhouse building decorated for George V's Silver Jubilee 1935

Edna, Thelma and Ivy stressed that the infirmary housed some excellent medical facilities, including an outstanding maternity unit and children's ward. But its link with the Workhouse was a stigma hard to overcome. In the 1960s, when the Workhouse building was demolished and the brand new Dewi Sant Hospital built on its site, this bleak reputation lingered. The town's older residents were always reluctant to enter the building, fearful they would never emerge.

Wheatsheaf Pub, Graig c1970

As the 20th century progressed the Graig gradually declined as a commercial centre, but it was after the 1960s that the greatest changes occurred. The Maritime Colliery closed in 1961, and its site was later cleared and landscaped to make way for a small industrial estate. Asked about the greatest changes they'd seen on the Graig, Edna, Thelma and Ivy lamented the demolition of the complex of streets and narrow passageways around the Wheatsheaf pub at the bottom of the Graig in the 1970s and 1980s. They felt this had destroyed some of the unique character of the place.

The other trend they'd observed was the gradual loss of old established families, to be replaced by newcomers who tended to move on after a short time. This trend has continued in the years since the women were interviewed. In 1931 the population of the Graig was around 7,000.

Today, it is less than half that, and many of the remaining terraced houses are let to the local student population attending the University of South Wales at Treforest.

David Gwyer (Assistant Curator)

Aerial view of the Griag, 1936